And Burn my shadow away…

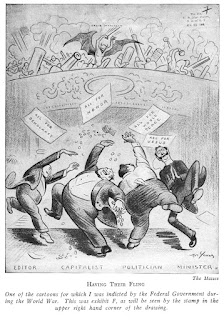

Erving Goffman wrote an often referenced paper in 1952 entitled On Cooling the Mark Out. To understand this election year, LI advises our readers to read it.

The paper begins by describing the confidence game, which involves roping a mark, getting him to invest, financially, in some scheme or game, and clearing him out. At this point, the confidence gang has the option of simply leaving the mark behind. But…

“Sometimes, however, a mark is not quite prepared to accept his loss as a gain in experience and to say and do nothing about his venture. He may feel moved to complain to the police or to chase after the operators. In the terminology of the trade, the mark may squawk, beef, or come through. From the operators' point of view, this kind of behavior is bad for business. It gives the members of the mob a bad reputation with such police as have not. yet been fixed and with marks who have not yet been taken. In order to avoid this adverse publicity, an additional phase is sometimes added at the end of the play. It is called cooling the mark out After the blowoff has occurred, one of the operators stays with the mark and makes an effort to keep the anger of the mark within manageable and sensible proportions. The operator stays behind his teammates in the capacity of what might be called a cooler and exercises upon the mark the art of consolation. An attempt is made to define the situation for the mark in a way that makes it easy for him to accept the inevitable and quietly go home. The mark is given instruction in the philosophy of taking a loss.”

This pretty much describes the two cases we have before us this election year. The ruinous Bush years involved two con games that were entwined one with the other. We have the con game that keeps us in Iraq, one fully supported by the ropers in – the governing elite – and we have the con game that is now busting, the full fruit of Bush’s economic policy, which involved minimizing regulation of the financial markets while maximizing the amount of money they had to play with. In this way, credit could fill up that hole where compensation from work used to be – and so productivity gains could be appropriated at a much higher rate by the richest, while home equity could be tapped, via mortgages, for the good life by the debtors.

Goffman points out that the mark’s psychology is a tricky one. To an economist, it might just look like utility maximization. But…

“In many cases, especially in America, the mark's image of himself is built up on the belief that he is a pretty shrewd person when it comes to making deals and that he is not the sort of person who is taken in by any thing. The mark’s readiness to participate in a sure thing is based on more than avarice; it is based on a feeling that he will now be able to prove to himself that he is the sort of person who can "turn afast buck." For many, this capacity for high finance comes near to being a sign of masculinity and a test of fulfilling the male role.”

Warmonger psychology unerringly follows this primitive but powerful gender program. This army of pissants shows all the signs of having had trouble emerging from the sack of their twelve year old selves, when, apparently, the separation anxiety produced by throwing out their G.I. Joe doll became frozen in place. A smaller contingent of this army – much smaller – forms the viewing core of financial porno tv networks, like CNBC. These people actually believe that they are part of the confidence game gang, which is how they came to mouth a rote optimism that had as little relation to reality as your average automobile ad has to how you would really drive an automobile.

“A mark's participation in a play, and his investment in it, clearly commit him in his own eyes to the proposition that he is a smart man. The process by which he comes to believe that he cannot lose is also the process by which he drops the defences and compensations that previously protected him from defeats. When the blowoff comes, the mark finds that he has no defence for not being a shrewd man. He has defined himself as a shrewd man and must face the fact that he is only another easy mark. He has defined himself as possessing a certain set of qualities and then proven to himself that he is miser ably lacking in them. This is a process of selfdestruction of the self. It is no wonder that the mark needs to be cooled out and that it is good business policy for one of the operators to stay with the mark in order to talk him into a point of view from which it is possible to accept a loss.”

Goffman’s analysis of the mark points us to the form of the presidential election – that Halloween for grownups. Whoever the candidates are, they will represent wings of an established power that has made suckers of the vast majority of the population over the last four … eight… twelve…sixteen years. An established power that has assured America that the costs of running this empire will always be paid by third parties – whether these consist of tropical countries dealing with the forces unleashed by the American appetite for junking up the atmosphere with CO2, or Middle Eastern countries struggling with the yoke of American oppression in a more direct form – the soldier in their face, the mercenary who shoots them for fun in the traffic jam. Of course, this isn’t true. Those costs will come back here. The cost of the Middle East adventure can be seen in the run up of oil prices, a very small intimation of a much larger and connected group of problems that come with running out of prestige and power in a large area of the world while at the same time maximizing the number of people who hate you. As for CO2, it will turn out that melting the glaciers in the west during the drought cycle was not a good idea. The American west, overpopulated, overdeveloped, its water overpromised, is going to learn the lesson of the Hummer, too. This isn’t just something we can sluff off on Bangladesh.

“For the mark, cooling represents a process of adjustment to an impossible situation - situation arising from having defined himself in a way which the social facts come to contradict. The mark must therefore be supplied with a new set of apologies for himself, a new framework in which to see himself and judge himself. A process of redefining the self along defensible lines must be instigated and carried along; since the mark himself is frequently in too weakened a condition to do this, the cooler must initially do it for him.

One general way of handling the problem of cooling the mark out is to give the task to someone whose status relative to the mark will serve to ease the situation in some way. In formal organizations, frequently, someone who is two or three levels above the mark in line of command will do the hatchet work, on the assumption that words of consolation and redirection will have a greater power to convince if they come from high places.”

It is going to be an excellent year for spectators.